AVID looks at Stephen Shaw's Follow-up Report

The first Shaw review was a landmark publication in the ongoing work towards reform of detention in the UK. Shaw interpreted his terms of reference broadly and produced detailed and powerful recommendations. NGOs working with migrants and people in detention welcomed his findings and recommendations, which were broadly accepted by the Government. The impression since has been that progress towards reform has been slow, and that some policies implemented as a result have actually made things worse for people in detention.

In his second review, Shaw looks at progress towards the recommendations in his first review, and has also broadened the range of subjects under consideration. He finds very limited evidence of improvements, but some evidence of a shift in thinking and culture in the Home Office, which has yet to embed. Shaw’s report reiterates much of what is concerning about the way in which detention operates in the UK. We find ourselves at a moment in time with ever more reports, reviews, and analyses which show not only that indefinite detention is harmful and unjust, but also that it is over used. Radical reform is long overdue.

Strategy and ‘mission creep’

Diane Abbott has spoken recently, recalling the time when government first began to implement the use of detention in a significant way. Parliamentarians were assured, she says, that detention would be for as short a time as possible and only when removal was imminent. However, the trouble with chipping away at something so fundamentally important as the right to liberty, is that it can become politically and institutionally normalised. This leads to the expansion we have seen of the use of detention in the UK, the longer periods of detention, the increasing size of the detention estate (until very recently) that have been concurrent with an increasingly toxic conversation around migration in the UK.

Shaw has criticised the lack of strategy in the development and management of the detention estate, calling it ‘happenstance’. He points out that the number and location of centres is not based on practical considerations or evidence of the number of spaces needed in order to effectively meet the supposed need the Home Office has for immigration control, but much more haphazardly. This creation of spaces in which to detain people, in our target driven culture, will inevitably lead to those spaces being filled. This moves decision making away from the absolute principles of last resort prior to imminent removal, into something more routine. If the state of the use of detention in the UK is something that has been drifted into, decisive action is needed now to prevent further harm and to reinforce fundamental rights and principles.

‘Dignity’ and ‘policy tweaking’

The ‘dignity’ of those held in detention formed a significant part of the Home Secretary’s response to the Shaw Review, which partially addressed concerns within Shaw’s report about conditions inside centres and the level of care provided. However, while tinkering with the edges of the detention system, the basis upon which people are being detained remains utterly unjust. We welcome any improvement to the way in which people are treated but it’s important to step back and consider where the action of detaining someone sits within an effective and humane immigration system. Improving standards should be automatic but not an end goal.

The impact of detention

Throughout Shaw’s Review, there are references to the impact of detention, the continuing vulnerability of those held in detention, the increasingly lengthy periods of detention, and the fact that detention frequently serves no clear purpose when more than half of those detained are later released. More than that, though, we know that the spectre of detention hovers over people working to regularise their immigration status in the UK.

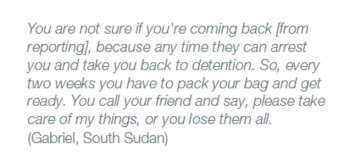

The recent Red Cross report illustrates the impact of detention on the lives of those subject to it, the fear and uncertainty of reporting to the Home Office (the point at which many are detained) is damaging and pervasive in its impact on people’s lives. The damage caused by indefinite detention goes much wider than the central issue of the rights and experiences of those subject to it.

The recent Red Cross report illustrates the impact of detention on the lives of those subject to it, the fear and uncertainty of reporting to the Home Office (the point at which many are detained) is damaging and pervasive in its impact on people’s lives. The damage caused by indefinite detention goes much wider than the central issue of the rights and experiences of those subject to it.

Vision, leadership and meaningful reform

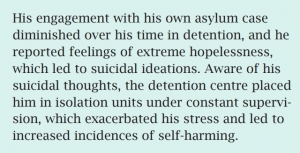

The recommendations put forward by NGOs - including AVID - in their evidence to Shaw, many of which are mentioned in his report, need to be seen in the round in how they present practical steps towards values that should be prioritised in reforming detention. The issue of vulnerable people in detention has been of huge concern to AVID and many others, with our research showing that vulnerability is a truly dynamic issue which is tied to the length of time spent in detention.

A time limit

Much discussion around the idea of a time limit has, as Shaw says, coalesced around the idea of a 28 day limit. Shaw makes it clear that he doesn’t feel he has seen evidence to support 28 days, and it is a shame that he has not engaged further with this issue considering the acknowledged fact that indefinite detention is a significant factor in vulnerability.

Reducing time spent in detention to 28 days immediately addresses the profound suffering faced by someone held in detention for days, weeks, months and years, who literally does not know how long they will be there. It ensures that decisions to detain are used more genuinely as a last resort and when removal is imminent.

Assessing vulnerability

The suggestions around the UNHCR Vulnerability Screening Tool, which AVID and others have advocated for, and which Shaw seems to support, set out a way of engaging with the dynamic nature of an individual’s vulnerability and ensuring that they are properly assessed and cared for throughout the process. This includes ensuring appropriate support is in place throughout and that they are not wrongly subjected to detention.

Providing alternatives

The discussion around ‘alternatives to detention’ has, on the evidence available, identified case-working models which support a person to engage with the often complex legal processes they must go through in regularising status in the UK, and then to be empowered in considering options going forward as an effective model. This is incredibly difficult for those whose lives are disrupted by being subjected to detention.

This is not only the evidence based response, it is also the common sense, humane and respectful approach to working with any person in any context. More than that, centreing these values in developing effective alternatives sets out a vision for a different way in which this country could manage migration.

Shaw has endorsed this approach in his report, which is being taken forward by the Home Office in the form of a pilot project. Crucially, as Detention Action have pointed out, any alternative must lead to a significant

reduction in the numbers of people being detained.

(Syed Case study - from ‘Rethinking Vulnerability in Detention: a Crisis of harm’)

What’s next?

We have seen greater scrutiny of detention in the past few years than ever before, and the pace has certainly picked up in 2018. The coming months will see the Joint Committee on Human Rights conduct its inquiry, which will look at the issue of a time limit, alongside a number of other questions. The Home Affairs Select Committee has yet to publish its report, which began last year and has gradually broadened in scope from focusing on specific centres to looking at the entire system of detention. We will be paying close attention to the Home Office response and the commitments set out by the Home Secretary in response to the Shaw Review, which we outlined here. The upcoming immigration bill is another opportunity to finally implement real and meaningful change. Maintaining momentum now is crucial and we hope to see more discussion, engagement and action on the basis of the Shaw Review, as well as to see the political consensus around detention reform grow to finally push for real, lasting change to this broken system.